Turning Tribal Knowledge Into a Company Asset

Transform tribal knowledge into a company asset! Learn how to document processes, avoid costly mistakes, and build a scalable, resilient business. Read now!

Turning Tribal Knowledge Into a Company Asset

There’s a moment I see over and over again.

A business has grown to 35 or 40 people. The owner is proud, and rightly so. The early chaos has “settled.” Work gets done. Customers are mostly happy. There are one or two people everyone goes to for answers, but that feels like a strength: “Thank goodness we have her. She knows everything.”

And then one of those people leaves.

Suddenly, the company discovers it has been running on something that was never really an asset at all.

It was tribal knowledge.

When your company knows things you don’t

My working definition is simple:

Tribal knowledge is when your company knows things that you don’t.

You think things are happening a certain way because “people know what to do.” But the moment you change something—an employee, a system, a policy—you find out they don’t.

In the very early days, tribal knowledge is actually useful. With eight people, the owner is the octopus in the middle: eight arms, direct visibility, quick improvisation. You don’t need a process for everything; you can just turn your head and ask.

But tribal knowledge has a built-in ceiling.

Without real, shared process, most companies hit a hard limit somewhere around 35–50 employees. That’s the point where:

- Everybody has their own version of “the right way.”

- Error rates and re-dos stop being cute and start being expensive.

- The owner’s mental model of “how we work” diverges from what’s actually happening on Tuesday at 3:15 p.m.

You can build a 10–15 person team on memory and good intentions. You cannot build a scalable machine on stories in people’s heads.

The commissions file that wasn’t there

Let me tell you about one situation that still makes my teeth clench.

There was an accounting employee—highly competent, deeply unpopular. Everything somehow went through this person. They were unbending, hard to work with, and eventually, for the sake of morale, the company let them go.

Life moved on. Until commission time.

It turned out that this person was the only one who actually knew how salesperson commissions were calculated in practice. The logic wasn’t documented in any policy. It wasn’t cleanly embedded in the accounting system. No one could even find the master spreadsheet.

You can imagine the feeling in the building as the days ticked by.

Salespeople are the lifeline of most companies. When they don’t get paid, or don’t trust the way they’re getting paid, they do not think, “Ah, what an interesting process gap.” They think, “They don’t value me.”

After a frantic search, the file eventually surfaced in someone else’s directory, inside a subfolder, with an innocuous filename—plus a message basically begging people not to delete it again.

The spreadsheet had existed all along. The knowledge of where it lived, what it did, and how it worked had not.

Everyone was relieved. Nobody was happy.

The emotional punchline in the room was: “We should have done something about this sooner.”

The real tribal knowledge tax

When a key employee walks out with undocumented process in their head, the real cost isn’t the severance—it’s everything that comes after:

- The weeks of reconstruction time while everyone reverse-engineers what they were doing.

- The months of elevated errors and customer credits while you discover all the little steps nobody knew about.

- The hiring scramble when you can’t even clearly describe the job you’re trying to fill.

Most owners chalk this up to “turnover is expensive” without realizing they’re paying a tribal knowledge tax on every departure.

One bad exit can easily burn 2–3% of annual revenue in cleanup and friction. If you ever sell, it gets worse: buyers discount key-person risk hard, sometimes knocking 10–20% off what they’d otherwise pay for the business.

A serious process-mapping effort takes a few weeks of focused time. The cost of not doing it is the next “oh no” day—and there’s always a next one.

“We’re excellent” vs. what the data says

Another company, a manufacturer, prided itself on excellence. High quality, reliable delivery, the works.

They also had one person who quietly sat at the center of more than anyone realized. Before that person left, leadership discovered just how little they understood about what this person actually did when they realized they needed their help to define the job for a replacement.

That’s the first alarm bell: when an employee has to help you understand what their own job is.

After they left, the damage didn’t show up as a dramatic explosion. It showed up as a slow, uncomfortable pattern:

- More jobs being redone.

- More credits and discounts issued to make things right.

- More “we’re sorry, we’ll do better this time” conversations.

None of those individual events bankrupted the business. But they quietly chewed through time, money, and customer goodwill.

And there’s a deeper cost: identity.

Internally, this company believed, “We’re a shop that strives for excellence.” The reality, revealed by one departure and a hole in their process, was that they had been running on luck more than they thought.

Tribal knowledge has a nasty habit of exposing that gap between who you think you are and what the data would say about you.

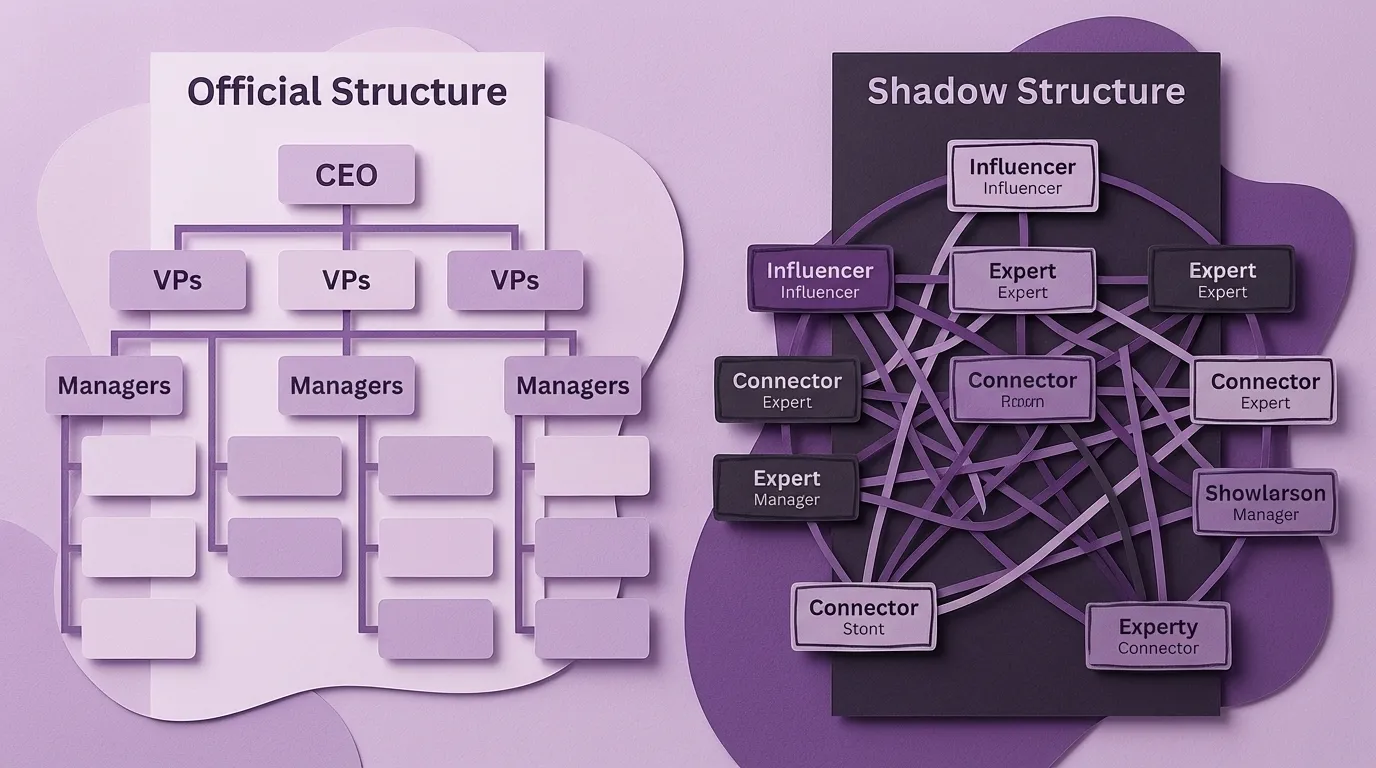

The shadow org chart

On paper, most companies have an org chart. Boxes, titles, reporting lines.

Tribal knowledge operates on a different diagram.

There is always a shadow org chart based on questions:

- “Who do I go to when this breaks?”

- “Who understands that spreadsheet?”

- “Who has the real answer to how we actually do X?”

You can spot the shadow org chart by looking for:

- The person cc’d on every “we’re not quite sure” email.

- The one whose desk has a constant trickle—or line—of people with questions.

- The tools that function as black boxes: the old Access database, the mysterious report, the Excel workbook everyone is slightly afraid to touch.

A black box in a business is any system where:

- Inputs go in.

- Outputs come out.

- Only one human can explain why.

Most owners underestimate how many black boxes they have until they start asking people, one by one:

- “Walk me through your day.”

- “How do you know what to do next?”

- “What do you do when you don’t know what to do?”

I’ve seen companies discover, almost by accident, that a quiet admin was downloading the entire client database to their personal machine every week just to reformat mailing labels. No one had told them to. No one had thought to ask whether they did.

On the org chart, unremarkable.

On the shadow org chart, absolutely critical.

When the software becomes the new Julie

A common mistake is buying software first and mapping processes later. That’s tribal knowledge in reverse—now the system is the black box.

You end up with:

- Workarounds nobody remembers the reason for.

- Turned-off features nobody understands.

- A widening gap between what the software can do and what your people actually do.

The software becomes the new Julie: the thing everything flows through that nobody really understands, wrapped in a few key power users who “speak its language.”

Instead of tribal knowledge living in someone’s head, it now lives in a tangle of configurations, custom fields, hidden reports, and habits. You’ve simply moved the problem, made it more opaque, and usually paid a subscription fee for the privilege.

The antidote is to understand reality first—and then build or configure systems to reflect it.

How we actually capture what people know

When we’re brought in to build an ERP or workflow system, the first job isn’t writing code. It’s reality capture.

A good session doesn’t start with “Tell me your process.” It starts with:

“Your company hired us to build a system around how you really work. The danger with software is that it does what we tell it to do, not what you actually do. So this is your chance to show us reality. No detail is too small—if we don’t hear about it, we can’t fix it.”

Then we ask them to show us their day on screen.

Not the aspirational version; the real one.

We watch where they click, which tabs they keep open, which spreadsheets they open with a little sigh, who they email for clarification. We ask childish “why?” questions whenever something glosses over a gap:

- “You said ‘I enter the commissions’—where do those numbers come from?”

- “You said ‘I check the exception list’—what is that, who maintains it, where does it live?”

We record it all. Then we feed the transcripts, carefully, into AI to help us:

- Identify actual processes, not the ones people think they have.

- Surface information silos—who sits at the center of what.

- Draft the first version of procedures that reflect how this specific company operates.

The key is context.

If you ask an AI, “Write me an SOP for purchase orders,” you’ll get a generic answer that looks tidy and means nothing. Your employees will read it, shrug, and go back to what they were doing.

If, instead, you give it dozens of interviews from your own people and say, “Now draft the PO process as we actually do it,” you get something very different: references to the real exception spreadsheet, the real cutoffs, the real constraints.

Now you’re not just “documenting tribal knowledge.” You’re documenting what you’re about to change.

When the system becomes the documentation

I once saw a 300-page orientation manual. That’s not onboarding; that’s a semester.

The assumption behind something like that is: “If we write everything down and make them read it, they’ll do it our way.”

They won’t.

Most of the time they’ll skim the first few pages, then learn the real job from whoever sits next to them.

One company handled this very differently.

They didn’t throw the big manual away; they cleaned it up and kept it as reference. But they stopped pretending it was the primary way new people would learn.

Instead, they built a custom system where the workflow was embodied in the screens themselves:

- A single page where you could handle an entire customer interaction without tab gymnastics.

- Forms whose structure roughly matched the actual timeline of the process.

- Guardrails that prevented actions out of order—no issuing a purchase order without the prerequisite steps.

And then they recorded about eight hours of training video showing real screens, real scenarios, narrated by real people doing the work.

Onboarding time dropped by about 50%.

This is what I mean when I say the system is the documentation.

The primary way of “learning how we do things here” moves from a thick narrative manual to a combination of:

- Working in a system that matches reality.

- Short videos or pages for context where needed.

- A small, accurate body of written SOPs that can be tested and audited.

And crucially, the system doesn’t just enforce what you’re not allowed to do. It also pays attention to what you never did:

- “This quote was created but never sent.”

- “This onboarding task is still open three days before the deadline.”

- “Nobody has followed up on this exception.”

Tribal knowledge is great at filling in gaps silently. Systems are great at saying, “By the way, there’s a gap here.”

As a bonus metric: put a decibel meter in your open office. If, after proper system and SOP work, the sound level drops because fewer people are shouting across the room for help, you’re on the right track.

Keeping it alive (and why clockwork matters)

Nothing in a business stays still. Markets change, tools change, people change. If your documentation and systems don’t evolve with them, you’re quietly drifting back into tribal territory.

You cannot rely on “we’ll update things whenever something changes.” That’s how you got into this mess in the first place.

You need something more boring and more reliable: clockwork.

- A quarterly or annual review of key processes on a fixed cadence.

- A short audit: pick a few workflows, talk to the people doing them, see if the system and docs still match reality.

- Fix what’s off. Repeat.

If you skip it, you’re telling everyone—including yourself—that this isn’t important.

You can also hook reviews to events: big customer wins, promotions, hires and departures, annual employee reviews. “Walk me through your day now—does what we’ve written still describe what you actually do?”

It takes discipline. Tribal knowledge is easier and more fun in the moment. It also goes away when people do.

Succession and the “oh no” day

Succession planning isn’t just estate planning for the business owner. It’s a very sharp test:

“If the owner were already on a beach somewhere and you were buying this company, could you run it based on what’s written down and built into the systems?”

If the honest answer is “no,” then tribal knowledge is now a discount line on your future valuation.

The bad news is, most small businesses don’t do succession planning. The good news is, you don’t have to eat the elephant in one sitting.

You can start by borrowing an idea from the accountability chart concept:

- Make a list of everything important that happens in the company—at a fairly granular level.

- Put names next to each thing. Real names, not titles.

- Stand back and look at where everything clusters.

The picture you get won’t look like your org chart. It will look like your dependency map.

Those clusters are where tribal knowledge is most concentrated—and where the “oh no” moment will hurt the most if someone leaves suddenly.

If that day comes and you’ve done none of this, the work is the same, just more stressful:

- Triage what threatens revenue and customer trust first.

- Interview everyone on the edges of the missing person’s work: the ones who fed them input and received their output.

- Reconstruct the process from the outside in.

- Document and adjust systems as you go so you don’t recreate a new single point of failure in someone else’s head.

Everyone is replaceable. Specific, undocumented knowledge isn’t. Your job is to move as much of that knowledge as possible from “inside someone” to “inside the company.”

Where to start

If you’re running a 20–150 person company, here’s a simple way to begin turning tribal knowledge into an asset instead of a risk:

- Spend a week quietly noticing who everybody goes to for answers. That’s your shadow org chart beginning to reveal itself.

- Pick a handful of processes that would hurt the most if their owners disappeared. Those are your first interviews.

- Record the walkthroughs. Use tools—including AI—intelligently to help you see patterns and draft your first real, specific SOPs.

- Make at least one small change in your system so that next time, the work is guided by the screen, not just by memory.

- Put a recurring reminder in your calendar to revisit all of this. Don’t trust yourself to “remember.”

Tribal knowledge itself isn’t bad. It’s how craft and culture start.

The problem is when you stop there.

The real leverage comes when you take what only a few people know and turn it into something the company can own, test, improve, and survive losing people with—without a line of panicked sales reps asking where the commissions file went, or a buyer quietly shaving 20% off your valuation because your best processes still live in somebody’s head.

Keywords

Related Articles

We Spent Days Fighting a Zebra Card Printer. So You Don't Have To.

Frustrated with Zebra ZC350 card printer integration? Dazzle, an open-source bridge, saves you time ...

Your Accounting Method Should Drive Your Software — Not the Other Way Around

Don't let your accounting software dictate your business. Learn how to choose the right accounting m...

Two Lines of Code That Fix Logging Spaghetti in Real JavaScript Systems

Tired of unreadable logs? Fix JavaScript logging spaghetti with just two lines of code! Add context ...