ERP for Small Businesses: What Actually Matters

Confused about ERP? This guide cuts through the jargon to reveal what ERP software *actually* does for small businesses, where it creates value, and where it destroys it.

ERP for Small Businesses: What Actually Matters

Most articles about ERP software read like they were written by someone who's never run a business.

They list features. They explain what acronyms stand for. They tell you that "supply chain management" and "better customer service" are benefits—as if you didn't already know that managing your supply chain and serving customers well would be good things to do.

None of that helps you make a decision.

What helps is understanding what ERP software actually does in practice, where it creates real value, and where it quietly destroys the things that make your business work. That's harder to write about, because it requires admitting that the answer depends on your specific situation—and that "industry-leading" solutions often make things worse.

What ERP Software Is Actually For

Strip away the jargon and an ERP system does one thing: it puts information that currently lives in different places into one place.

Customer data, inventory levels, orders, invoices, employee records, project status—all accessible from a single system instead of scattered across spreadsheets, email threads, and the head of whoever's been there longest.

That's it. That's the core value proposition.

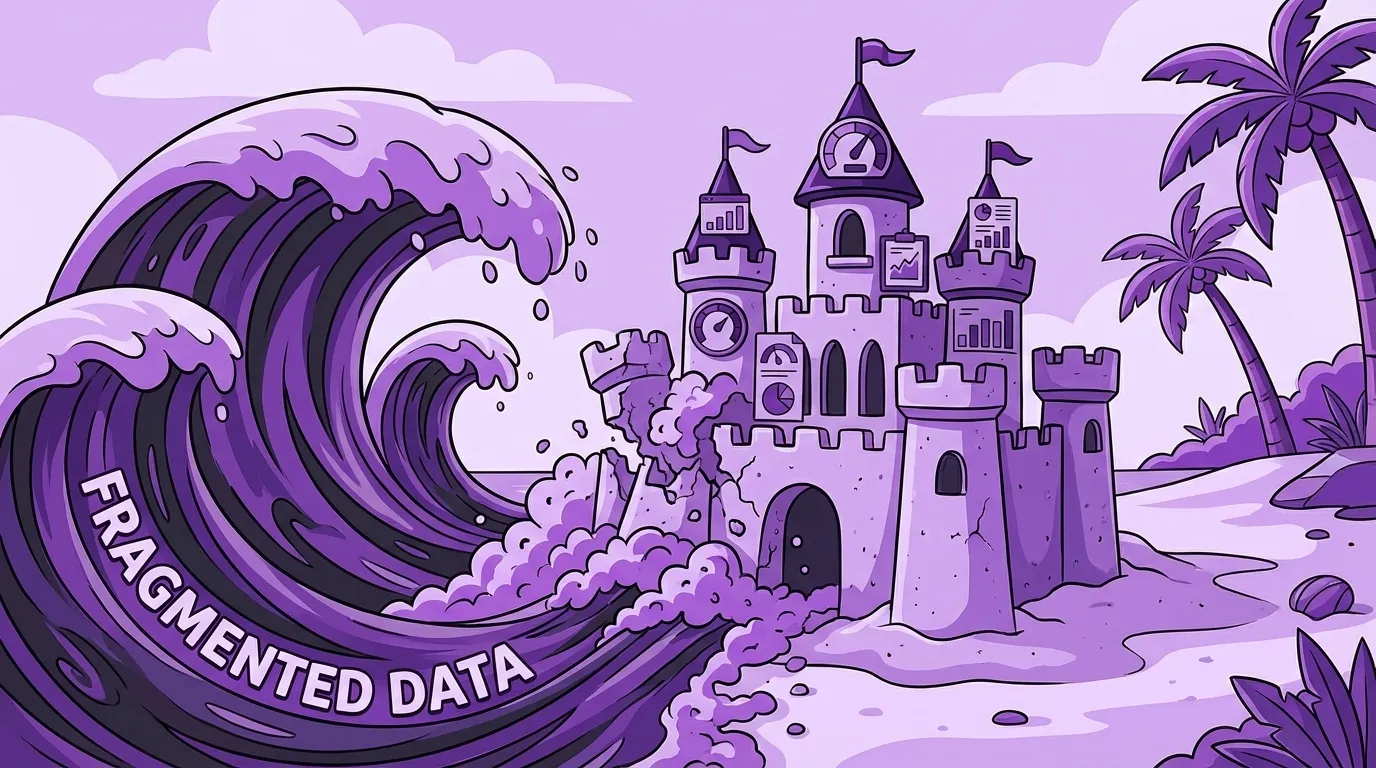

Everything else—the dashboards, the reports, the automation, the "business intelligence"—is downstream of that consolidation. If your information is fragmented, those features are building on sand. If your information is unified and accurate, those features might actually be useful.

The question isn't whether consolidation would help. For most 15–150 person companies running on a patchwork of tools that don't talk to each other, it would. The question is whether the specific system you're considering will consolidate your information in a way that matches how you actually work—or whether it will force you to change how you work to match its assumptions.

That distinction is everything.

The Promise vs. The Reality

Here's what vendors tell you ERP software will do:

Streamline your supply chain. Monitor procurement, inventory, and fulfillment from one screen.

Improve customer service. Everyone sees the same customer data, so anyone can help.

Automate accounting. Financial processes happen without manual intervention.

Speed up order processing. No more re-keying information between systems.

Enable better decisions. Real-time data means you can see what's actually happening.

All of this is technically true. And all of it is mostly useless for evaluating whether a specific system will work for you.

The reality is that every one of those benefits depends on implementation—on how well the system fits your actual workflows, how clean your data is going in, how much your people actually use it, and whether the "automation" matches what you need or just creates new manual work to fix what the automation got wrong.

I've seen ERP implementations deliver everything on that list. I've also seen them make every single item worse. The difference wasn't the software. It was whether anyone understood the real problem before they started buying solutions.

Where ERP Systems Actually Create Value

In my experience, the businesses that get real ROI from ERP software share a few characteristics:

They're drowning in manual data transfer. If the same information gets typed into three different systems, and someone spends hours every week reconciling the discrepancies, consolidation solves a real problem. The value isn't abstractit's the hours you get back and the errors you stop making.

They've outgrown tribal knowledge. When only two people know how things actually work, and one of them is thinking about retiring, you have a fragility problem. A well-implemented system captures process knowledge in a form that survives personnel changes.

They need visibility they can't currently get. If answering "how profitable was that project?" requires pulling data from four different places and hoping the numbers line up, unified reporting is genuinely valuable. But only if you're actually going to use it to make decisions.

They're ready to standardize (some) processes. This is the tricky one. ERP systems impose structure. That's a feature when your lack of structure is causing problems. It's a bug when your "non-standard" process is actually your competitive advantage.

Notice what's not on this list: "They need to look more professional" or "Competitors are doing it" or "The current system is old." Those might be true, but they're not reasons. They're rationalizations.

Where ERP Systems Destroy Value

The failure modes are predictable enough that I can usually spot them in the first conversation.

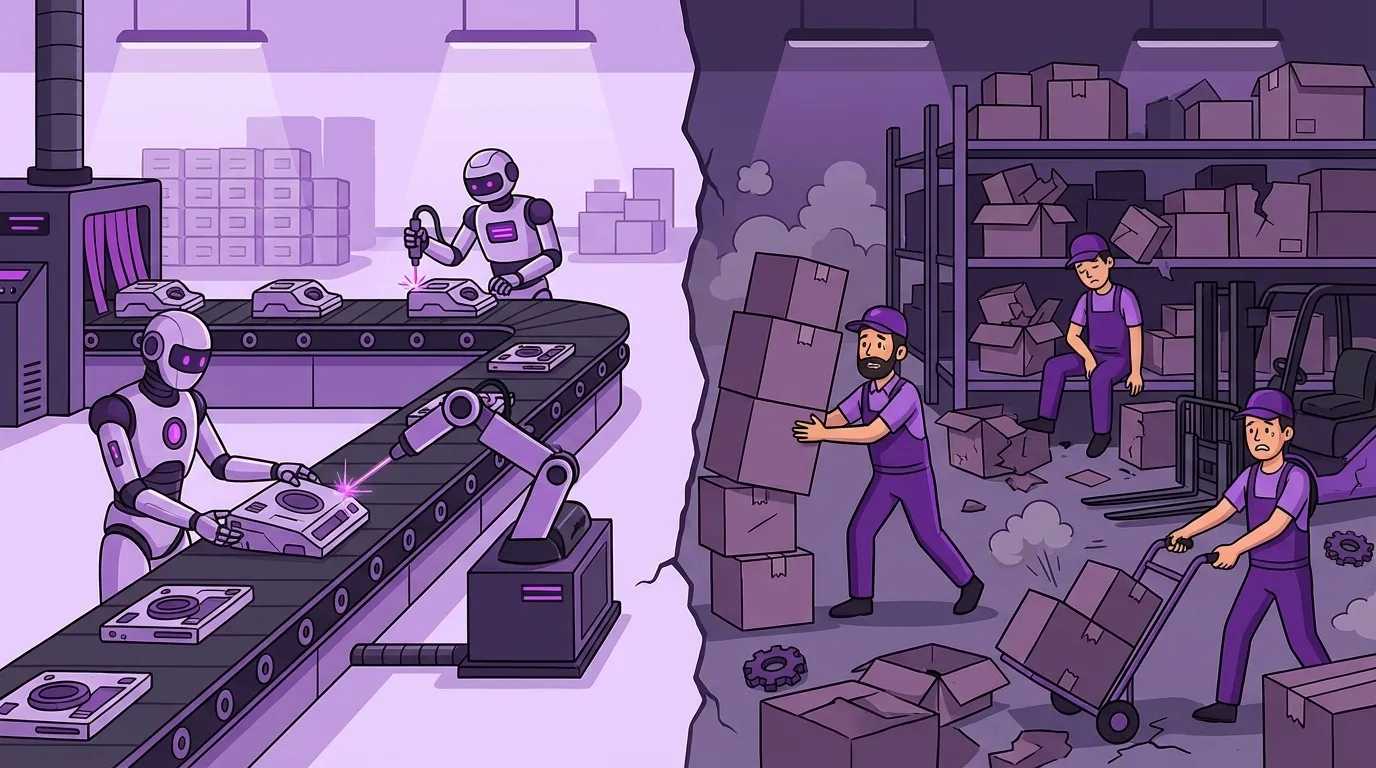

Forcing conformity on differentiation. If how you handle customer requests is why customers choose you, and the new system forces you into a standard workflow, you've just automated away your competitive advantage. I've seen this happen more than once. The software worked perfectly. The business got worse.

Creating complexity that exceeds your capacity. Enterprise ERP systems are designed for companies with dedicated IT staff and project managers. A 20-person company doesn't have those people. The system sits half-configured, and you're paying enterprise prices for spreadsheet functionality.

Solving the wrong problem. Sometimes the issue isn't fragmented data. It's a broken process that would be broken in any system. Software doesn't fix process problems. It digitizes them. Faster dysfunction is still dysfunction.

Underestimating the human transition. The technical implementation is the easy part. Getting your people to actually change how they work—that's where implementations die. If leadership isn't willing to spend real time on adoption, you're buying expensive shelfware.

The Questions That Actually Matter

Forget feature comparisons. Before you evaluate any specific system, answer these:

What problem are we actually solving? Not "we need an ERP." What specific pain are we trying to eliminate? What would success look like in operational terms?

What do we do differently than competitors? And does any of that difference live in processes the new system would standardize? If so, be very careful.

Who will own this internally? Not just the purchase—the implementation, the adoption, the ongoing care and feeding. If the answer is "we'll figure it out," you're not ready.

What's our realistic capacity for change? Be honest. How much bandwidth do your key people actually have? How many other initiatives are competing for attention?

What happens if this doesn't work? Can you get your data out? Can you go back to what you had? What's the exit cost?

These questions are harder than comparing features. They're also more useful.

On-Premise vs. Cloud (It Matters Less Than You Think)

Vendors will make this sound like a momentous architectural decision. For most small businesses, it's not.

Cloud means someone else manages the servers. Lower upfront cost, subscription pricing, accessible from anywhere, updates happen automatically. The tradeoff is that you're dependent on the vendor and your internet connection, and you may have less control over when changes happen.

On-premise means you manage the servers. Higher upfront cost, more control, works without internet. The tradeoff is that you need IT capacity to maintain it, and upgrades are your problem.

For a typical 15–150 person company without dedicated IT staff, cloud usually makes more sense. You're not in the server management business. But the deployment model matters far less than whether the software actually fits how you work.

Don't let this question distract from the ones that matter.

On "Industry-Specific" Software

This is where I have strong opinions.

When a vendor says their software is "built for your industry," it sounds like a selling point. They've encoded best practices. They understand your world. The software will teach you to be better at what you do.

I've never seen evidence that it works that way.

What "industry-specific" usually means is that the software was designed for the average company in your industry. The features reflect what most companies need, configured the way most companies work.

If your competitive advantage comes from operating like everyone else, that's fine. But if how you work is why customers choose you, then "industry standard" software is a trap. You're not buying efficiency. You're buying conformity.

I learned this running a service organization years ago. We tried the leading industry-specific platform, expecting it to teach us best practices. Productivity dropped 10%. The software didn't match how we worked. The "best practices" it enforced weren't better than what we'd already figured out. People invented workarounds, and we were back to undocumented processes—just with a fancier login screen.

The discovery process—figuring out what we actually needed—turned out to be more valuable than any feature list. But we took the expensive way around.

Build vs. Buy (The Real Question)

Some companies should build custom software. Most shouldn't—at least not for everything.

The honest answer is that you build when the return justifies the cost, same as any business decision. The problem is that people underestimate the costs on both sides.

The hidden cost of buying is forcing your business to adapt to software instead of software adapting to your business. You lose workflows that differentiate you. You inherit someone else's assumptions. Your competitive advantage erodes toward the industry average.

The hidden cost of building is the human work: explaining what you actually need, then getting your people to adopt the change. Most companies underestimate this by a factor of three or four.

My general advice: buy commodity tools without overthinking it. Accounting, email, payroll—these are solved problems. Don't get creative.

But for software that touches your core operations—how you quote, deliver, and get paid—at least consider whether off-the-shelf solutions will help or hurt. The answer depends on whether your processes are genuinely standard or genuinely different.

Before You Start Evaluating

Here's something you can do this week that will make every vendor conversation more useful.

Pick one process—not the most complex, but the most important. The one that directly touches revenue.

Watch someone actually do it. Not the documented version. The real version.

Note every system they touch. Every copy-paste. Every workaround. Every "I just check with Sarah on this part."

Time the parts that aren't the work itself—moving information, re-keying data, waiting for answers, fixing manual errors.

Multiply that by how often it runs. Put a rough dollar figure on the hidden cost.

Now you have something concrete. When a vendor demos their solution, you'll know whether it actually solves your problem or just moves it somewhere else. You'll know what questions to ask. And you'll know whether the implementation effort is worth it.

The feature list is the easy part. Knowing what you actually need is the hard part. Do that work first, and the evaluation gets a lot simpler.

Keywords

Related Articles

We Spent Days Fighting a Zebra Card Printer. So You Don't Have To.

Frustrated with Zebra ZC350 card printer integration? Dazzle, an open-source bridge, saves you time ...

Your Accounting Method Should Drive Your Software — Not the Other Way Around

Don't let your accounting software dictate your business. Learn how to choose the right accounting m...

Two Lines of Code That Fix Logging Spaghetti in Real JavaScript Systems

Tired of unreadable logs? Fix JavaScript logging spaghetti with just two lines of code! Add context ...